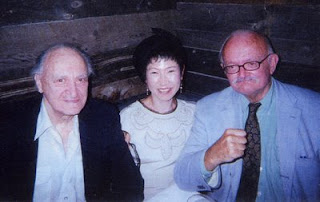

Note: Last year, Vince met for an interview with Robert Thompson, the distinguished Yale professor who is writing his highly anticipated history of mambo. A lively correspondence has ensued.

Below is an excerpt, discussing Vince’s early passion for Casino de la Playa’s classic “Bruca Manigua.” The first Arsenio Rodriguez tune ever recorded, “Bruca” was “a landmark in the development of Cuban popular music,” as Ned Sublette details in his book,

RF Thompson:

26 December, 2008

One thing that amazes me about your career is how you picked up on “Bruca Manigua” back in 1939 and started playing it on harmonica. What pulled you into this song? Lyrical feel? Afro-Cuban savor? All of the above and more? What I want to know is how the lyrics hit you. They were in an intricate mixture of bozal (slave idiom in creolized Spanish) and creolized Ki-Kongo, flaunting words like fwiri and mundele. Beyond the Afro-Atlantic complexity, did you dig “Bruca” mainly because of the melody?

You had to be one of the hippest men in

Have a brilliant New Year,

Bob

Part One:

“Bruca Manigua”

Indiambo congori, omelenko, la-di-o-de, coro mi yare—where do these sounds come from that they drown out the music and the culture I was born into? They forever forbid my disloyalty to them—they made me a religious person even though I knew nothing of their meaning. How did they capture me so gently, using their very concealed implications to control me?

From early childhood, as a special-education candidate due to lead poisoning that profoundly affected my hearing, my efforts to understand my world led me to become fascinated with the unknown—with what was escaping me in life. I sought shelter in the mysterious shadows that both hid me and comforted me as an adopted outcast. I grew up further and further from the path that others took. This attitude that was part of my formation set me aside from a society that I could handle easily as long as an odd quality and mystery remained a part of me. I neither belonged entirely to Africa or to America in the sense that my hearing evolved on a different level from normal—which in turn placed me astride a larger world that I balanced myself on like a circus bareback rider holding two galloping horses under his control, with one foot on each.

This effective bipolarity assisted rather than hindered my learning in that it demanded twice the effort—not to conform, but to understand, to balance my intellectual equilibrium. Thus, while I could not understand or speak

The sounds and vocabulary of

This esoteric burden manifested itself in the release I found in response, in the physical expression encompassed in dancing. Not American-style dancing or classical footwork, but in the dancing that is African. This came about guided by the music that I came in contact with. Initially, my family preferred opera to popular music but for me opera represented a musical establishment that at the same time jived with the everyday music.

When in 1936 and onward I caught bits of African music coming from abroad, from the islands and

The drum began to be something I needed biologically, it seemed. It filled the empty quality of deafness the way the gigantic Wurlitzer organ at the Paramount Theater filled the house. To the rafters.

Part Two:

“Bruca Manigua” and Mother

“El Manisero”… What is this manisero, this repetitious melody that is heard everywhere and where did it come from, everyone wondered back in 1937? “…un cucuruchu de mani…” What is a “cucuruchu”? By the time I learned that the song was what we today call a singing commercial, the “Peanut Vendor” passed on, only to be replaced by “La Cucaracha.” “Ya no puede caminar…,” another odd “Spanish” song, this one about a roach. When “La Cucaracha” crawled away, we were ready for a Latin tune called “Siboney” whose more sublime lyrics spoke plaintively of a black slave’s ordeal. Its melodic beauty was like a schoolgirl’s lament, lacking the basic ugliness of the horrors of slavery.

As “Spanish music” became more popular, we heard, for example, “El Plato Roto.” “Pancho tuvo que pagar / lo que rompio Rafael”…songs with sexual implications like double-entendre meanings wherein Pancho pays for what Rafael broke. El plato (plate, dish) and roto (broken) being a girl’s hymen. “El Bastidor” was another sly device, that sang of the hardness of a mattress as well as the durability of the male organ.

But these playful or sugary reflections did not have the blood and guts power of a song that spoke out the truth, loud and clear. They seemed to conceal, to hesitate or only hint at the slaves’ oppression. Just as the iron chains that restricted movement to just the four steps of la conga, there was no room in the lyrics to encourage rebellion, that is, until “Bruca Manigua. “Sin la libertad no puedo vivir / siempre tan maltrata”! This song touched and alerted a sensitive nerve that lay dormant in me, even having heard the sadness in the impoverished peanut vendor’s cry.

“Bruca” had sounded the key note and was followed soon by other brazen messages: “Yo Soy Karabali,” “Negro Nananboro,” Chano Pozo’s “Guaguina Yerabo,” Piniero’s “Yambo,” “Yambu” and “Lamento Borincano”… The ponderous quality of “Bruca” and the others, with all the drama that they exposed, still had more to follow even while holding me in vicarious empathy. Instead of doing my math, I played and replayed those records on my old phonograph, chained to it.

The full result of my original exposure and consequent entrancement with Afro-Latin music did not hit me until “Juan Fue Pa’ La Guerra,” with Daniel Santos singing “Quehago si vuelvo / y no encuentro a mi mama?” The composer was Pedro Flores. Here was a demoralizing song that ran counter to the US Army’s policy of allowing only militarized motivation for the sake of patriotic encouragement. This very touching song ended with the sad words, “What will I do should I return (from the war) and not find my mother (alive)?”

Since I was about to leave for the army, these sharp words were suddenly pertinent, more personal even those Miguelito Valdes sang in Arsenio Rodriguez’s “Bruca.” These words that included one’s mother hit home in two ways: the universal and the personal…the love that Latin sons in particular have for their mothers, and the son speaking not of his likely death in the army, but of his mother’s pain in not seeing her son again…his mother’s own dolorous ending…not his own pain over her death.

Such gut-wrenching lyrics exposed the quality of the culture that was behind the music. It being a sentimental blessing that produced such love, whether black or not.

This all surfaced and came together as a conscious awareness that I correlate with whenever I am in the physical presence of the people and their Afro-Latin music, or when alone with my conscience.